On 17 January 2024, the Australian Tax Office (ATO) released the updated draft tax ruling, TR 2024/D1 setting out its characterisation of payments related to software and other intangible property rights. This draft ruling comes three years after the first draft was provided in TR 2021/D4.

What is the relevance of TR 2024/D1?

This draft ruling is especially important for Australian subsidiaries of multinational groups that make payments to a foreign owner or licencee of a copyright (or other IP) for the right to earn income relating to the use of, or right to use the software.

Where a part (or all) of these payments constitute royalties per TR 2024/D1, they will be subject to royalty withholding tax, which must be deducted from these payments and remitted to the ATO. If a company pays royalty payments offshore but fails to withhold and remit the Australian withholding tax, then the company will be denied a deduction for these payments for income tax purposes until the withholding tax is paid.

What does the latest draft ruling include?

The latest ruling is significantly more comprehensive than the first draft and now addresses the following important points:

- The interplay between the royalty definition contained in domestic tax laws and those in the Double Tax Agreements (DTAs) in place between Australia and other treaty countries.

- It distinguishes the ATO position from the position contained in the OECD commentary, which is commonly referred to by OECD countries to assist in the interpretation of DTAs.

- It includes additional detail on when apportionment may be justifiable where an undissected software-related payment may relate to aspects other than the use of a copyright.

- It addresses when a payment related to the distribution of tangible goods that include embedded software components constitutes a royalty payment.

What will the application of the ruling look like in practice?

The ATO sets out its reasoning via the use of the following two illustrative examples:

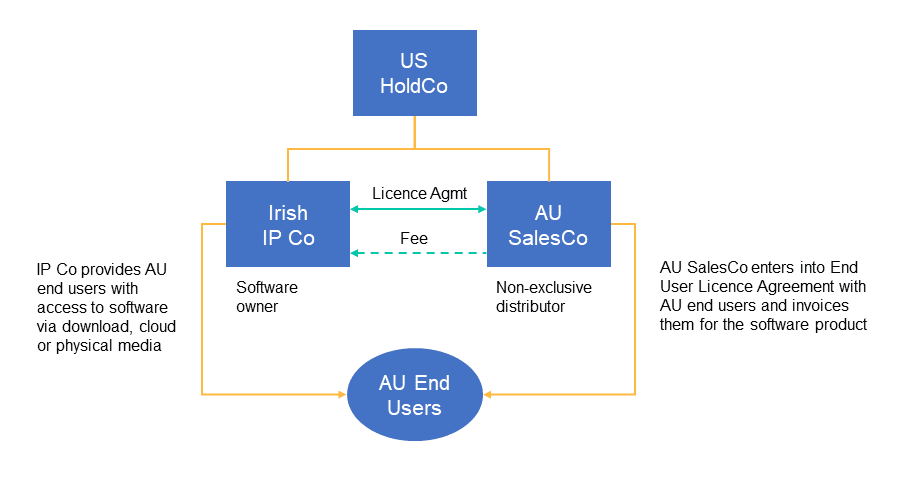

Scenario 1

Under Scenario one, the ATO’s view is that payment of the fee by AU SalesCo to Irish IP Co constitutes a royalty under the applicable DTA. The ATO’s rationale is that, even though the software is communicated to the end user by the IP Co, before this occurs, AU SalesCo must enter into an End User Licence Agreement (EULA) with the customer, which means that AU SalesCo authorises the communication of the programs to the end users.

This ‘authorisation right’ which IP Co has provided to AU SalesCo falls within the ambit of the exclusive rights of the copyright owner, making any payment associated with this right a royalty.

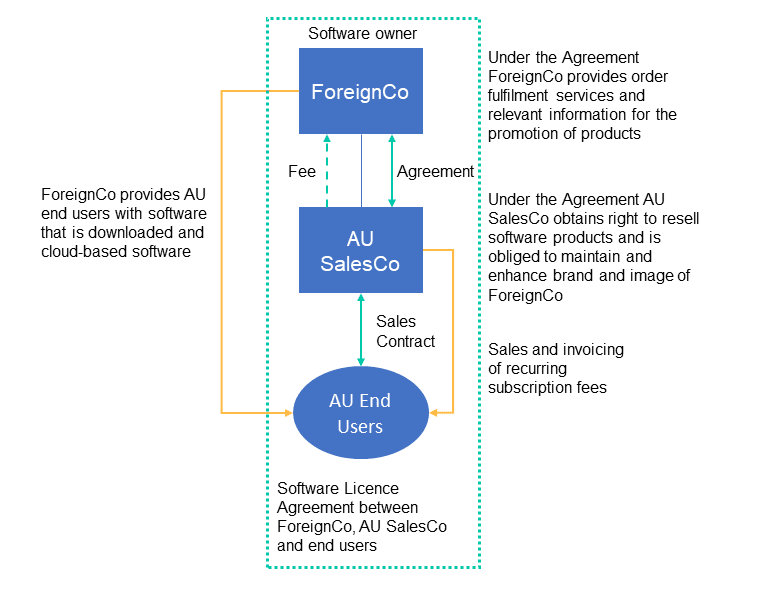

Scenario 2

Under Scenario two, the ATO’s view is that the payment of the fee by AU SalesCo to ForeignCo constitutes a royalty.

This is because Au SalesCo obtains the rights to use ForeignCo’s branding, gains access to their information and know-how of the software products and uses the copyright to enter into a commercial rental agreement (periodic licence) with end users.

The ATO notes that if there is evidence that establishes a value of the distribution rights independent to IP rights, the fee could be reasonably apportioned.

This scenario emphasises that payments for services ancillary to the use of IP will also be subject to royalty withholding tax.

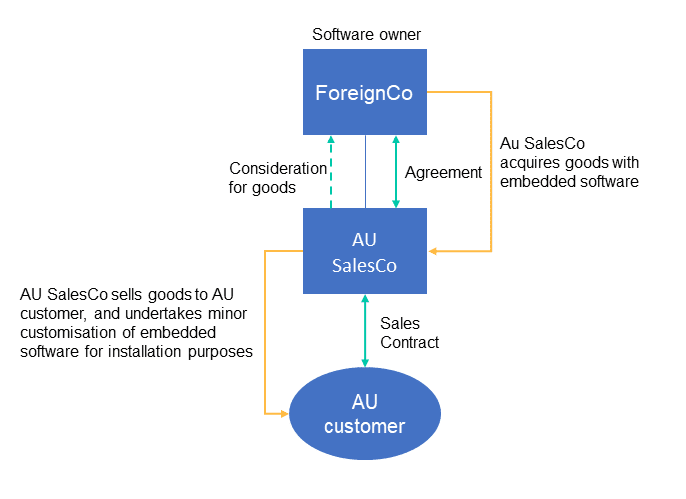

Embedded software

The ruling also addresses when payments for tangible goods that include a software component (referred to as embedded software) will be viewed as a royalty. The ATO adopts a similar ‘rights-based’ approach to software sold via other mediums (cloud or discs, etc.). If the distributor of the goods that have embedded software uses, or is granted a right to use, the copyright or other IP right related to the software, the payment (or part thereof) will constitute a royalty. A reasonable apportionment between the goods and software components will be required.

This could arise when AU SalesCo, the Australian distributor, is provided with a right to modify or adapt the embedded software. This is a point of difference to the OECD approach, which states that minor customisation by a distributor for purposes of installation should not result in the payment being classified as a royalty.

What is the difference between the ATO and OECD interpretations?

The view of the ATO with respect to payments related to software distribution arrangements appears to deviate from the OECD position. According to the OECD, the rights (in the copyright) acquired by a software distributor are limited to those necessary for the intermediary to distribute the relevant program. This is different from the right to exploit the software copyright.

The OECD’s view is that businesses should treat payments derived from these distribution rights as business profits, rather than royalties, regardless of whether the copies being distributed are on tangible media like discs, or in electronic form (e.g. cloud based).

The ATO has interpreted the OECD commentary on an overly narrow basis. It does not take into account that the OECD commentary envisages that a distributor will obtain certain rights related to the copyright. However, as long as these rights are limited to those necessary to achieve the distribution, the payment should not constitute a royalty.

Applying the OECD approach to scenario one and two above, AU SalesCo does not reproduce the software to the end user. In all instances, this is undertaken by the copyright owner. AU SalesCo is thus supporting the copyright owner with the distribution of software products in Australia.

AU SalesCo may be provided with rights (such as authorisation rights per scenario one) to achieve this, but if it can be shown that these are limited to the rights required by AU SalesCo to facilitate the distribution, then the payment should not be viewed as a royalty under the OECD interpretation.

Where the ATO interprets the ambit of a DTA in a manner that differs from the OECD guidance, a question arises as to whether an IP owner who disagrees with the interpretation applied, may seek resolution under the mutual agreement procedure article, where available.

Our closing thoughts

While TR 2024/D1 was released in draft form once again and is open for public consultation until 1 March 2024, the ATO has not deviated from their position in TR 2021/D4. It is, therefore unlikely that the ATO will significantly change their views should this ruling be finalised.

Any Australian companies that operate in global groups where software is sold to end users in Australia, including software embedded within tangible goods, should be re-assessing their inter-group arrangements to determine the rights and obligations between the parties. Where undissected payments are made in respect of various rights provided by a copyright holder, an analysis will need to be performed to assess a reasonable basis of apportionment.

TR 2024/D1 does not provide a commencement date and states that it will apply both before and after its date of issue. This provides significant uncertainty to taxpayers. For large multinational groups (country-by-country reporting groups and significant global entities), it could also result in potential failure to lodge penalties. The payment of royalties offshore triggers additional annual compliance obligations which may not have been met if this ruling is applied retrospectively.

To discuss how the new draft ruling may impact you, contact your local William Buck advisor.